Solving the 8-queens problem

This tutorial will showcase how to use some of the building blocks provided by LP to solve a combinatorial problem.

In this example, we will solve the 8-queens puzzle. This is a constraint satisfaction problem in which the goal is to place 8 queens in a chess board such that neither of them check each other.

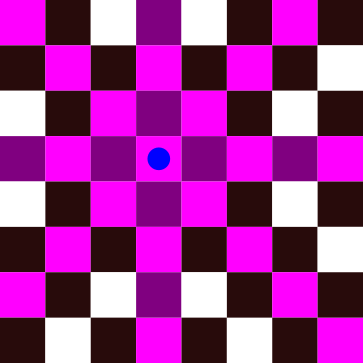

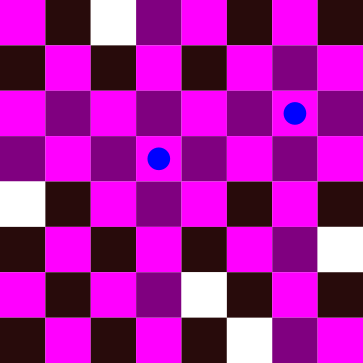

In the figure above, we have placed a queen represented by a blue dot. All conflicting cells have been highlighted. The problem becomes harder when we add more queens to the board:

Implementing the solution

We can solve this problem using a Genetic Algorithm (GA) that deals with the constraints, using a steady-state approach and logging statistics on every iteration.

We will use the following modules:

using Statistics

using EvoLP

using OrderedCollectionsDealing with constraints

To implement the solution, we need to handle the constraints in some way. For this problem, we can divide the constraints in vertical, horizontal and diagonal clashes between the queens.

Interestingly enough, the vertical and horizontal clashes can be dealt with by using a vector of permutations where the genes (index of the vector) represent a column and the alleles (values the index can take) represent the row used in that column:

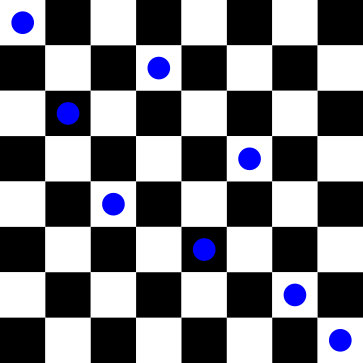

For the phenotype above, the genotype representation would look like this:

x = [1, 3, 5, 2, 6, 4, 7, 8]The queen in the first column is in row 1. The queen in the second column is in row 3, and so on.

EvoLP contains a convenient permutation_vector_pop:

julia> @doc permutation_vector_popWe can now use the generator to initialise our population:

pop_size = 100

population = permutation_vector_pop(pop_size, 8, 1:8)

first(population, 3)3-element Vector{Vector{Int64}}:

[3, 7, 4, 8, 2, 1, 5, 6]

[5, 4, 7, 6, 2, 3, 1, 8]

[8, 6, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7]To deal with the diagonal constraints, we can use the fitness function.

The penalty of a queen is the number of queens she can check. The penalty of a board configuration would then be the sum of all penalties of all queens, and this is what we want to minimise. So let's build our fitness function step by step.

Assume a queen $q$ is in a position $(i, j)$. Then, we can define the diagonal neighbourhood as the following:

- Top-left: $(i-1, j-1)$

- Top-right: $(i-1, j+1)$

- Bottom-left: $(i+1, j-1)$

- Bottom-right: $(i+1, j+1)$

We can then use this information to iterate in all directions and check how many queens are there in the diagonals.

If we do this for every queen $q$, then we will count some of the clashes twice. It is a good idea to create a set of these clashes so that we can sum them afterwards.

function diag_constraints(x)

# rows are values in x

# columns are indices from 1:8

fitness = []

for q in 1:8

tl = collect(zip(x[q]:-1:1, q:-1:1))

tr = collect(zip(x[q]:-1:1, q:1:8))

bl = collect(zip(x[q]:1:8, q:-1:1))

br = collect(zip(x[q]:1:8, q:1:8))

constraints = Set(vcat(tl, tr, bl, br))

delete!(constraints, (x[q], q))

q_fit = sum([(i, j) in constraints ? 1 : 0 for (i, j) in zip(x, 1:8)])

push!(fitness, q_fit)

end

return sum(fitness)

endTo handle the corners and not specify "emtpy" diagonals, we consider the position $(i,j)$ of a queen to count as a "clash" itself. This means that a queen in $(1,1)$ will consider $(1,1)$ as the top-left diagonal, and $(i,i), i \in [1,8]$ as the bottom-right diagonal (again, including itself). We later remove these additional constraints via delete! and proceed normally.

Using the same configuration as before, we have the following conflicting positions:

We can test our fitness function diag_constraints on this board and see the number of conflicts in total:

test = [1, 3, 5, 2, 6, 4, 7, 8]

diag_constraints(test)10Going through each queen $q_i$ (with $i$ being the column number), we have the following number of conflicts: $q_1 = 2$, $q_2 = 1$, $q_3 = 0$, $q_4 = 1$, $q_5 = 1$, $q_6 = 1$, $q_7 = 2$, $q_8 = 2$

Evolutionary operators

We now need to choose our evolutionary operators: what we will use for selection, crossover and mutation.

However, since we're dealing with permutations, we are restricted to use specific operators that do not end up destroying feasible solutions and therefore violate our constraints. EvoLP contains some operators that can deal with permutation-based individuals:

julia> @doc TournamentSelectorTournament parent selection with tournament size ``k``.julia> @doc OX1RecombinatorOrder 1 crossover (OX1) for permutation-based individuals.julia> @doc SwapMutatorSwap mutation for permutation-based individuals.We can now instantiate them and continue.

S = TournamentSelector(5);

C = OX1Recombinator();

M = SwapMutator();Logging statistics

We can use the Logbook to record statistics about our run:

statnames = ["mean_eval", "max_f", "min_f", "median_f"]

fns = [mean, maximum, minimum, median]

thedict = LittleDict(statnames, fns)

thelogger = Logbook(thedict)Logbook(LittleDict{AbstractString, Function, Vector{AbstractString}, Vector{Function}}("mean_eval" => Statistics.mean, "max_f" => maximum, "min_f" => minimum, "median_f" => Statistics.median), NamedTuple{(:mean_eval, :max_f, :min_f, :median_f)}[])Constructing our own algorithm

And now we are ready to use all our building blocks to construct our own algorithm. In this case, we will use a steady-state GA: instead of replacing the whole population, we will generate a fixed amount of candidate solutions and keep the best n individuals in the population each iteration.

Let's do a summary then:

- The representation is a vector of permutations of integers with values in the closed range $[1,8]$.

- To select the parents, we use the

TournamentSelectoroperator with a tournament size of 5. - To recombine the parents, we use the

OX1Recombinatoroperator. - To mutate a candidate solution, we use the

SwapMutatoroperator. - To select the survivors, we replace the worst individuals.

- With a population size

pop_sizeof 100. - With a random initialisation using the generator

permutation_vector_pop. - We will use a crossover probability of 100%.

- And a mutation probability of 80%.

We can then build our algorithm in a function, and use EvoLP's Result type for the return:

function mySteadyGA(logbook, f, pop, k_max, S, C, M, mrate)

n = length(pop)

# Generation loop

for _ in 1:k_max

fitnesses = f.(pop)

parents = select(S, fitnesses) # this will return 2 parents

parents = vcat(parents, select(S, fitnesses)) # Extend the list with 2 more parents

offspring = [cross(C, pop[parents[1]], pop[parents[2]])] # get first kid

offspring = vcat(offspring, [cross(C, pop[parents[3]], pop[parents[4]])]) # get 2nd

pop = vcat(pop, offspring) # add to population

# Mutation loop

for i in eachindex(pop)

if rand() <= mrate

pop[i] = mutate(M, pop[i])

end

end

fitnesses = f.(pop)

# Log statistics

compute!(logbook, fitnesses)

# Find worst and remove

worst1 = argmax(fitnesses)

deleteat!(pop, worst1)

deleteat!(fitnesses, worst1)

# And do the same again

worst2 = argmax(fitnesses)

deleteat!(pop, worst2)

deleteat!(fitnesses, worst2)

end

# Result reporting

best, best_i = findmin(f, pop)

n_evals = 2 * k_max * n + n

result = Result(best, pop[best_i], pop, k_max, n_evals)

return result

endTo try our new algorithm, we just need to call its function with the appropriate arguments:

result = mySteadyGA(thelogger, diag_constraints, population, 500, S, C, M, 0.8);EvoLP provides convenient functions that we can use to get information about a result:

@show optimum(result)

@show optimizer(result)

@show f_calls(result)

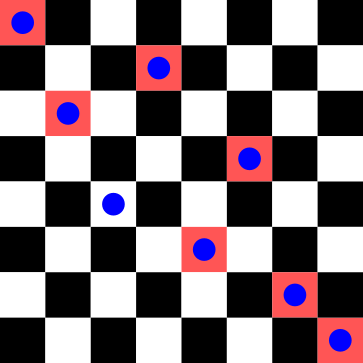

thelogger.records[end]optimum(result) = 0

optimizer(result) = Any[5, 1, 8, 6, 3, 7, 2, 4]

f_calls(result) = 100100

(mean_eval = 9.392156862745098, max_f = 20, min_f = 0, median_f = 8.0)And this is just a helper function to visualise our result as a chess board:

function drawboard(x)

b = fill("◻",8,8)

for i in 1:2:8

b[i,2:2:8] .= "◼"

end

for i in 2:2:8

b[i, 1:2:8] .= "◼"

end

for (i,j) in zip(x,1:8)

b[i, j] = "♛"

end

for i in 1:8

println(join(b[i,:]))

end

enddrawboard(optimizer(result))◻♛◻◼◻◼◻◼

◼◻◼◻◼◻♛◻

◻◼◻◼♛◼◻◼

◼◻◼◻◼◻◼♛

♛◼◻◼◻◼◻◼

◼◻◼♛◼◻◼◻

◻◼◻◼◻♛◻◼

◼◻♛◻◼◻◼◻